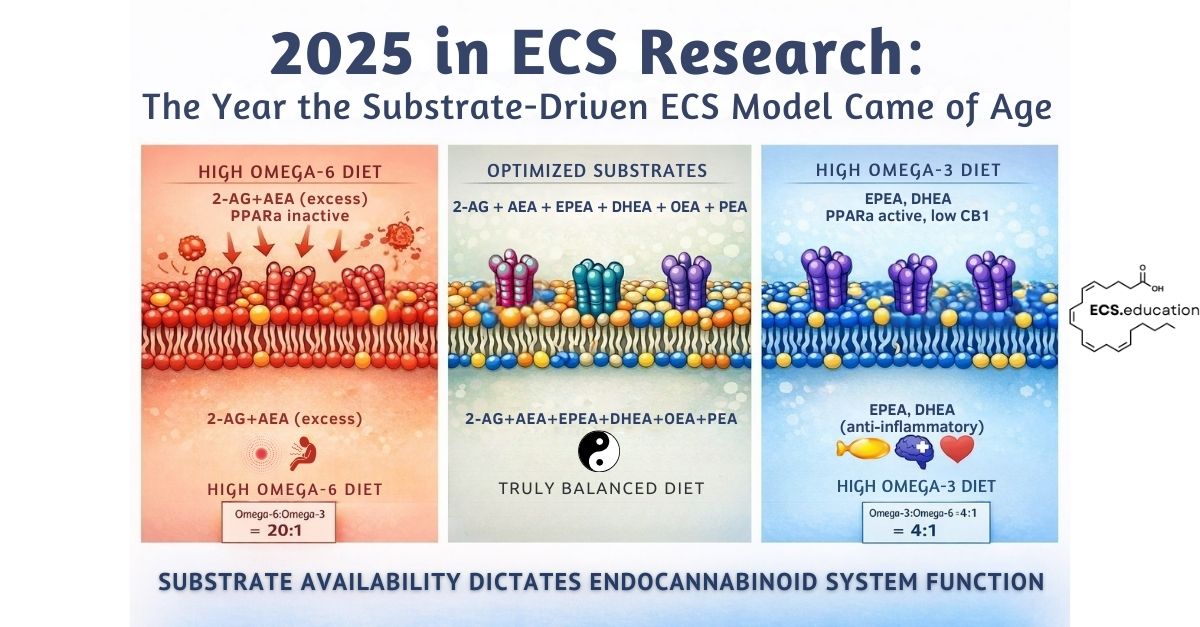

Endocannabinoid system substrate—specifically membrane fatty acid composition—is the primary determinant of CB1 receptor function, not genetics or receptor density.

Key takeaways (2025):

- Diet remodels membranes; membranes determine ECS capacity.

- Omega-3 can restore CB1 signalling after injury (e.g., adolescent alcohol exposure models).

- High-fat/omega-6 patterns can elevate gut endocannabinoid tone and reinforce feeding loops.

- “More endocannabinoid” isn’t automatically therapeutic (FAAH inhibitor PTSD trial).

- Substrate effects are receptor-diverse (CB1, TRPV1/TRPA1, PPARα) and context-dependent.

For years, I’ve been making the case that endocannabinoid system function is not primarily about receptor density or genetic variants, it’s about substrate availability. The composition of fatty acids in cell membranes determines how much 2-AG and anandamide your body can synthesize, how efficiently those molecules signal, and ultimately how well the system performs its homeostatic duties.

Until recently, this remained a mechanistic hypothesis with limited direct experimental validation. Sure, we had decades of nutritional biochemistry showing that dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids end up in membranes, and we knew that endocannabinoids are synthesized on demand from those very same membrane lipids. But the explicit, causal demonstrations linking dietary fatty acid intake to altered ECS function were sparse.

2025 changed that. This year brought an unprecedented convergence of evidence from disparate research groups working across different species, disease models, and therapeutic contexts. From alcohol-damaged brains to dairy cow reproduction, from post-infarction inflammation to PTSD treatment failures, the common thread was unmistakable: membrane fatty acid composition governs ECS capacity, and substrate context determines therapeutic outcome.

What follows is not an exhaustive review, but rather a curated tour through eleven studies published in 2025 that collectively validate the substrate-driven ECS framework. These papers didn’t just add incremental detail, they fundamentally shifted how we should think about endocannabinoid biology.

Omega-3 Rescues the ECS After Alcohol Damage

Let’s start with one of the cleanest demonstrations of dietary fatty acids directly modulating ECS architecture. Serrano and colleagues published work in June showing that omega-3 supplementation rescues long-term endocannabinoid system dysfunction caused by adolescent binge drinking (Serrano et al., 2025).

The setup was elegant. Adolescent mice subjected to intermittent ethanol exposure show persistent brain omega-3 depletion and CB1 receptor dysfunction that lasts well into adulthood. The question was whether replenishing omega-3 during the withdrawal period could reverse the damage.

It could. Omega-3 supplementation increased CB1 receptor density at hippocampal presynaptic terminals, restored CB1-stimulated G-protein signaling, and recovered endocannabinoid-dependent synaptic plasticity. Cognition improved alongside the molecular rescue.

And why does this matter? It shows us that omega-3 fatty acids are not just substrate for endocannabinoid synthesis. They are structural components of the membrane environment where CB1 receptors must insert, traffic, and function. When membranes are depleted of omega-3, CB1 receptor signaling fails—not because the receptors themselves are defective, but because the lipid environment they depend on is compromised.

This is substrate-driven biology at its most direct. You cannot fix a broken ECS by simply adding more agonist or blocking degradation. You have to restore the membrane substrate pool that allows the system to operate properly in the first place.

Excess ECS Activation Impairs Reproduction in Dairy Cows

If you needed confirmation that this substrate framework scales across species and physiological contexts, look no further than dairy cattle. Dos S Silva and colleagues reported in April that omega-3 supplementation during late pregnancy and early lactation dampens ECS activation in bovine ovarian follicles—and improves reproductive outcomes (Dos S Silva et al., 2025).

Specifically, cows supplemented with omega-3 fatty acids showed decreased CB1 and CB2 receptor expression in preovulatory follicles, reduced anandamide and 2-AG levels in follicular fluid, and lower complement protein and inflammatory marker expression in granulosa cells. Fertility improved.

At first glance, this seems paradoxical. Isn’t the ECS supposed to be beneficial? Why would reducing endocannabinoid tone improve reproduction?

The answer lies in understanding that the ECS is a homeostatic system, not a universally beneficial one. In the context of high omega-6, low omega-3 Western-type diets, the system becomes chronically overactivated. Excess 2-AG synthesis—driven by abundant membrane arachidonic acid—creates an inflammatory, dysregulated environment in reproductive tissues.

Omega-3 supplementation doesn’t “block” the ECS, it rebalances it. By reducing membrane arachidonic acid availability and providing alternative EPA/DHA substrates, it normalizes endocannabinoid tone. Less 2-AG synthesis in this context is therapeutic.

This is a critical point often missed in receptor-centric models: substrate depletion and enzymatic modulation are viable therapeutic strategies, not just receptor agonism or antagonism.

High-Fat Diets Drive Intestinal Endocannabinoid Overactivation

The dairy cow study showed that high omega-6, low omega-3 diets cause ECS overactivation in reproductive tissues. The same mechanism operates in humans, but the primary site of dysfunction is the gut. Vari and colleagues reviewed the evidence in May, documenting how high-fat Western diets increase intestinal endocannabinoid tone and drive metabolic disease (Vari et al., 2025).

When you consume fat-rich meals, intestinal epithelial cells synthesize endocannabinoids from dietary fatty acids. High-fat feeding increases CB1 receptor expression in the gut and elevates local 2-AG and anandamide levels. These endocannabinoids signal to the brain via the vagus nerve, promoting further fat intake. It’s a positive feedback loop: dietary fat → intestinal endocannabinoids → increased appetite for fat → more dietary fat.

In the context of high omega-6 intake (the Western dietary pattern), this loop amplifies. Abundant linoleic acid becomes membrane arachidonic acid, which becomes 2-AG, which drives overconsumption of calorie-dense foods. Diet and exercise fundamentally reshape ECS signaling through substrate dynamics—obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome follow.

But there are counterbalances. Oleic acid—the monounsaturated fat abundant in olive oil—generates oleoylethanolamide (OEA), an endocannabinoid-like molecule that activates PPARα and promotes satiety. The endocannabinoidome extends well beyond AEA and 2-AG, encompassing a vast dietary signaling network. Similarly, omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA are direct PPARα ligands themselves, and their endocannabinoid derivatives (EPEA, DHEA) likely share this activity. High-oleic and high-omega-3 diets dampen appetite rather than amplify it. Substrate composition determines whether the intestinal endocannabinoid system drives you toward or away from overconsumption. Omega-6 dominance activates CB1 and promotes feeding, while omega-3 and monounsaturated fats activate PPARα and promote satiety.

This connects directly to the dairy cow findings. In both cattle and humans, excess omega-6 relative to omega-3 creates pathological ECS overactivation. In cows, it impairs fertility. In humans, it drives metabolic disease. The solution is the same: rebalance membrane fatty acid composition by reducing omega-6 intake and increasing omega-3.

The intestinal endocannabinoid system isn’t dysfunctional in obesity—it’s responding perfectly to the substrate you’re providing. Change the substrate, and you change the signaling.

Omega-3 Endocannabinoids Synergize with the Microbiome

The substrate story gets even richer when you consider that omega-3 fatty acids don’t just generate different quantities of endocannabinoids, they generate different types of endocannabinoids with distinct pharmacology.

Mandal and colleagues demonstrated in January that omega-3-derived endocannabinoids (specifically EPEA and DHEA, synthesized from EPA and DHA respectively) work synergistically with short-chain fatty acids produced by gut microbiota to protect hippocampal neurogenesis from inflammatory damage (Mandal et al., 2025).

When exposed to pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6), hippocampal neurogenesis typically crashes and apoptosis increases. But omega-3 endocannabinoids combined with microbial SCFAs prevented this collapse. The protection was lost when either component was absent.

This matters because it shows that the ECS is not a standalone system. It’s integrated with metabolic and microbial inputs. Dietary omega-3 becomes membrane EPA/DHA, which becomes omega-3 endocannabinoids, which interact with microbial metabolites to regulate inflammation and tissue homeostasis.

You can’t optimize the ECS by tweaking one component in isolation. Substrate composition, microbial ecology, and metabolic state are all part of the same regulatory network.

Substrate Type Determines Which Receptors Are Activated Beyond CB1 and CB2

The substrate story extends well beyond cannabinoid receptors. Abate and colleagues demonstrated in March that polyunsaturated fatty acids and their endocannabinoid metabolites activate TRPV1 and TRPA1 ion channels—receptors involved in pain, inflammation, and neuroplasticity (Abate et al., 2025).

The team tested individual PUFAs (EPA, DHA, γ-linolenic acid) and their endocannabinoid derivatives (DHEA, EPEA, AEA, 2-AG) on human TRPV1 and TRPA1 channels. The results revealed that omega-3 and omega-6 endocannabinoids triggered different channel responses, and some effects only appeared after cells were primed with phorbol ester, meaning the cellular context determined whether channels could respond.

This matters because it shows substrate composition doesn’t just determine how much endocannabinoid you make. It determines which receptors and ion channels those endocannabinoids activate. Omega-3-derived EPEA and DHEA have different pharmacology than omega-6-derived 2-AG and AEA. The downstream effects (pain modulation, inflammatory signaling, neuroplasticity) depend on which substrate dominates your membranes.

TRPV1 and TRPA1 aren’t minor players. TRPV1 mediates heat pain and inflammatory hyperalgesia. TRPA1 responds to cold, mechanical stress, and inflammatory mediators. Both are expressed throughout the nervous system and peripheral tissues. If your membranes are loaded with omega-6, you’re producing endocannabinoids that activate these channels differently than if your membranes contain omega-3.

This tells us that the substrate-driven framework has expanded. It’s not only about CB1 and CB2 receptor signaling. It’s about the entire lipid signaling network—cannabinoid receptors, TRP channels, nuclear receptors—all responding to the fatty acid composition of your diet.

When Elevating Endocannabinoids Fails: The PTSD FAAH Inhibitor Trial

Now for the sobering part. If substrate availability is so important, shouldn’t elevating endocannabinoid levels always be therapeutic?

Not according to the PTSD trial published in September. Mayo and colleagues randomized 100 PTSD patients to receive either a FAAH inhibitor (JNJ-42165279) or placebo alongside internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (Mayo et al., 2025). FAAH is the enzyme that degrades anandamide, so blocking it predictably elevated AEA levels roughly tenfold.

But PTSD symptoms didn’t improve. Neither did depression, anxiety, or sleep quality. The drug successfully hit its target, elevated the endocannabinoid, and did absolutely nothing therapeutically.

Why? Because simply increasing the amount of anandamide circulating in the bloodstream tells you nothing about where that anandamide goes or what it does. Does it bind CB1 receptors? Does it get shunted into pro-inflammatory metabolites via COX-2? Does it activate TRPV1 and worsen anxiety? We don’t know, and the trial wasn’t designed to find out.

Substrate context determines whether CB1 activation is therapeutic or pathological, as seen in cardiovascular studies comparing acute cannabis effects to chronic dietary ECS dysfunction.

This is the exact lesson the substrate-driven framework teaches: it’s not about absolute levels of endocannabinoids. It’s about substrate composition, enzymatic context, and downstream metabolic fate. Elevating AEA in a person with chronic inflammation and dysregulated lipid metabolism may simply feed more substrate into pathological pathways.

The FAAH inhibitor failure is not a failure of the endocannabinoid hypothesis. It’s a failure of reductionist pharmacology that ignores substrate biology.

Arachidonic Acid: Context-Dependent Substrate Effects

Speaking of substrate fate, let’s talk about arachidonic acid—the omega-6 fatty acid that serves as the primary precursor for both 2-AG and AEA, and a host of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids.

Two papers published in 2025 perfectly illustrate why you cannot label arachidonic acid as simply “good” or “bad.” Its role is entirely context-dependent.

First, the bad news. Chen and colleagues showed in September that after myocardial infarction, membrane-released arachidonic acid fuels post-MI inflammation via a newly discovered PP5-5-LOX signaling axis (Chen et al., 2025). Arachidonic acid binds protein phosphatase 5, causing it to translocate to the nucleus where it dephosphorylates 5-lipoxygenase. Activated 5-LOX then converts arachidonic acid into leukotriene B4, recruiting B cells and amplifying cardiac inflammation. Blocking this pathway with either genetic PP5 knockdown or a pharmacological inhibitor improved post-MI outcomes.

In this context, arachidonic acid mobilization is pathological. The substrate is being funneled into pro-inflammatory eicosanoid synthesis rather than endocannabinoid signaling. Even common pharmaceuticals like acetaminophen work by modulating substrate conversion to 2-AG, demonstrating how substrate pathways determine therapeutic outcomes.

Now the good news. Peng and colleagues reported in December that arachidonic acid supplementation protects against diabetes-induced atrial fibrillation (Peng et al., 2025). Diabetic mice and AF patients both showed significantly decreased arachidonic acid levels. When supplemented, arachidonic acid reduced atrial remodeling, oxidative stress, and inflammation by activating the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. AF inducibility dropped.

Same substrate, opposite outcomes. In acute post-MI inflammation, abundant arachidonic acid feeds into 5-LOX and worsens pathology. In chronic metabolic disease, arachidonic acid depletion impairs antioxidant defenses and becomes pathological.

The lesson is unambiguous: substrate fate depends on enzymatic environment, tissue context, and metabolic state. You cannot predict therapeutic outcomes from substrate levels alone. You need to know what enzymes are expressed, what pathways are active, and where the substrate is being directed.

CBD Starves Cancer Cells of Lipid Substrates

Phytocannabinoids like THC and CBD are often framed as primarily receptor ligands, molecules that bind CB1 or CB2 and trigger downstream signaling cascades. But substrate-driven thinking suggests a different interpretation: these plant compounds are membrane-active lipid mediators that alter cellular fatty acid metabolism.

Supportive evidence came in February from Fu and colleagues, who showed that CBD inhibits ovarian cancer cell proliferation by disrupting lipid metabolism (Fu et al., 2025). CBD downregulated genes involved in fatty acid uptake (FABP5, LDLR) and lipid biosynthesis (SCD1, FASN, ACACA, SREBP1, PPARγ). The result: ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis.

Critically, supplementing the cells with exogenous unsaturated fatty acids or blocking CB1 receptors rescued them from CBD-induced death. This tells us CBD’s therapeutic effect in cancer is not purely about CB1 activation, it’s about starving the cells of membrane lipid substrates.

Cancer cells are metabolically greedy. They need enormous quantities of fatty acids to build membranes for rapid division. CBD interferes with that supply chain. It’s acting as a metabolic disruptor, not just a receptor agonist.

This reframes how we should think about cannabinoid therapeutics. Receptor binding is part of the story, but substrate modulation (changing what lipids are available, where they go, and what enzymes act on them) may be equally or more important.

Membrane Cholesterol Modulates CB1 Receptor Function

Membrane composition isn’t just about polyunsaturated fatty acids. Cholesterol, the most abundant lipid in neuronal membranes, also governs CB1 receptor function. This has been known experimentally for over a decade—cholesterol depletion using methyl-β-cyclodextrin alters CB1 signaling efficiency, and cholesterol enrichment reduces CB1-dependent activation (Bari et al., 2005; Oddi et al., 2011).

Vanegas and colleagues extended this mechanistic understanding in 2025 using molecular dynamics simulations, showing precisely how cholesterol binds to CB1 and modulates its function (Vanegas et al., 2025). Their computational models demonstrate that cholesterol stabilizes CB1 receptor oligomerization—the clustering of multiple receptors into functional units—and alters CB1 conformational states, affecting how efficiently the receptor couples to G-proteins and responds to ligands.

This computational work aligns with experimental findings in CB2, where cholesterol directly changes ligand pharmacology. A ligand that acts as a partial agonist in cholesterol-free membranes becomes an inverse agonist when cholesterol is present (Yeliseev et al., 2021). Membrane cholesterol content effectively tunes cannabinoid receptor sensitivity.

The clinical implications are worth considering, particularly given widespread statin use. Statins lower cholesterol synthesis and reduce membrane cholesterol content. Could chronic statin therapy alter CB1 receptor function? There’s already evidence that simvastatin disrupts CB1 expression and signaling in skeletal muscle cells (Kalkan et al., 2023), though whether this is mediated by cholesterol depletion or other mechanisms remains unclear.

This reinforces what the alcohol damage study showed: membrane lipid environment is not a passive backdrop. It’s an active determinant of receptor function. Omega-3 fatty acids provide the structural scaffold for CB1 insertion and trafficking. Cholesterol modulates receptor conformation and signaling efficiency. Both are required for proper ECS function.

Omega-3 as a Multi-Target Metabolic Modulator

If there’s a single take-home message from 2025, it’s this: omega-3 fatty acids are not a single-mechanism therapeutic. They are substrates that simultaneously reshape multiple metabolic pathways.

Li and colleagues published a comprehensive review in May detailing omega-3 mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases and epilepsy (Li et al., 2025). Omega-3 fatty acids competitively inhibit arachidonic acid metabolism through COX-2 and lipoxygenase pathways, generate anti-inflammatory specialized pro-resolving mediators like resolvins and protectins, modulate autophagy by inhibiting mTORC1 and promoting autophagic flux, and upregulate anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2.

None of these effects happen in isolation. They are all consequences of altering membrane fatty acid composition and shifting substrate availability across interconnected metabolic networks.

This is why isolated receptor interventions often fail while dietary interventions succeed. A FAAH inhibitor targets one enzyme in one pathway. Omega-3 supplementation restructures the entire lipid metabolic landscape over months of membrane remodeling.

It’s slower, less pharmacologically “clean,” and vastly more effective at the systems level.

What 2025 Taught Us About Substrate-Driven ECS Biology

So what does this all mean? Let me synthesize the lessons clearly.

First, membrane composition—not genetics or receptor density—is the primary determinant of ECS capacity. Polyunsaturated fatty acid ratios, cholesterol content, and lipid rafts all govern how well CB1 receptors function and what endocannabinoids your cells can synthesize. You cannot fix a broken ECS with drugs alone. You have to restore the membrane substrate pool.

Second, substrate type determines outcome. Omega-6-derived endocannabinoids activate CB1 receptors and drive feeding behavior. Omega-3 endocannabinoids activate TRP channels and PPARα, promoting pain relief and satiety. The downstream effects—inflammation, appetite, neuroplasticity—depend on which fatty acids dominate your diet, not just on absolute endocannabinoid levels. This is why the FAAH inhibitor failed in PTSD: elevating anandamide without addressing substrate context and enzymatic fate simply didn’t produce therapeutic benefit.

Third, context determines everything. Arachidonic acid fuels inflammation via 5-LOX in acute injury but protects against oxidative stress via Nrf2 in metabolic disease. High-fat diets increase intestinal endocannabinoid tone, driving overconsumption. Phytocannabinoids like CBD act as metabolic disruptors, not just receptor ligands. Same substrate, opposite effects depending on tissue, enzyme expression, and metabolic state. You cannot predict therapeutic outcomes from substrate levels alone.

Fourth, dietary interventions restructure the entire system. Omega-3 supplementation doesn’t just provide substrate. It competitively inhibits arachidonic acid metabolism, generates anti-inflammatory mediators, activates PPARα, modulates autophagy, and reshapes membrane lipid organization that governs dozens of receptors. This is why dietary interventions succeed where isolated receptor drugs fail—you’re restructuring the metabolic landscape, not targeting one pathway.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The clinical implications are straightforward but require a shift in thinking. Before initiating cannabinoid therapies, metabolic and inflammatory context should be assessed. Check plasma inflammatory markers, insulin sensitivity, dietary omega-6:omega-3 ratios. Understanding how to interpret fatty acid biomarkers correctly is essential for predicting therapeutic response.

Optimize membrane composition first. Omega-3 supplementation at 2-4 grams per day of EPA/DHA, sustained for 90-120 days to allow membrane remodeling. Reduce excess dietary linoleic acid. Support microbiome health with fiber and prebiotics to boost short-chain fatty acid production.

Then, and only then, consider receptor-targeted interventions—and do so with the understanding that substrate context will determine whether they succeed or fail.

The research published in 2025 makes one thing abundantly clear: the ECS is not a pharmacological target you manipulate with a conventional single molecule drug. It’s a metabolic system you support with substrates. Treat it accordingly.

References

Abate A, Santiago M, Garcia-Bennett A, Connor M. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their endocannabinoid-related metabolites activity at human TRPV1 and TRPA1 ion channels expressed in HEK-293 cells. PeerJ. 2025;13:e19125. Published 2025 Mar 24. doi:10.7717/peerj.19125

Chen Z, Song J, Feng S, et al. Arachidonic acid fuels inflammation by unlocking macrophage protein phosphatase 5 after myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. Published online September 4, 2025. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf493

Dos S Silva P, Butenko Y, Kra G, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation from late pregnancy to early lactation attenuates the endocannabinoid system and immune proteome in preovulatory follicles and endometrium of Holstein dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2025;108(4):4299-4317. doi:10.3168/jds.2024-25409

Fu X, Yu Z, Fang F, et al. Cannabidiol attenuates lipid metabolism and induces CB1 receptor-mediated ER stress associated apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):4307. Published 2025 Feb 5. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88917-1

Li M, Li Z, Fan Y. Omega-3 fatty acids: multi-target mechanisms and therapeutic applications in neurodevelopmental disorders and epilepsy. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1598588. Published 2025 May 30. doi:10.3389/fnut.2025.1598588

Mandal G, Alboni S, Cattane N, et al. The dietary ligands, omega-3 fatty acid endocannabinoids and short-chain fatty acids prevent cytokine-induced reduction of human hippocampal neurogenesis and alter the expression of genes involved in neuroinflammation and neuroplasticity. Mol Psychiatry. 2025;30(11):5338-5355. doi:10.1038/s41380-025-03119-5

Mayo LM, Gauffin E, Petrie GN, et al. The efficacy of elevating anandamide via inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) combined with internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2025;50(10):1564-1572. doi:10.1038/s41386-025-02128-w

Peng H, Xu S, Liu Y, et al. Arachidonic acid protects against diabetes-induced atrial fibrillation. Lipids Health Dis. Published online December 3, 2025. doi:10.1186/s12944-025-02815-z

Serrano M, Saumell-Esnaola M, Ocerin G, et al. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Mitigate Long-Lasting Disruption of the Endocannabinoid System in the Adult Mouse Hippocampus Following Adolescent Binge Drinking. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(12):5507. Published 2025 Jun 9. doi:10.3390/ijms26125507

Vanegas MJ, Gómez S, Cappelli C, Miscione GP. Exploring Membrane Cholesterol Binding to the CB1 Receptor: A Computational Perspective. J Phys Chem B. 2025;129(18):4350-4365. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.4c08076

Vari F, Serra I, Friuli M, et al. Pharmacological potential of endocannabinoid and endocannabinoid-like compounds in protecting intestinal structure and metabolism under high-fat conditions. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1567543. Published 2025 May 22. doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1567543