The body keeps secrets in its blood.

On a Tuesday morning in late 2024, 491 men and women stepped onto treadmills and cycle ergometers across several research institutions. None of them knew they were about to reveal something profound about the mechanics of human fitness. They simply pushed themselves toward exhaustion while their cardiovascular systems were interrogated—heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen consumption, all of it measured with clinical precision.

But the real story didn’t emerge from the heart rate monitors.

It emerged from the plasma.

A research team led by Mythri Ambatipudi used a specialized mass spectrometry platform to capture a snapshot of 886 bioactive lipids in each participant’s blood at rest and at peak effort. When they published their results in Physiological Reports this December, they revealed something that reads like a hidden mechanism in a Swiss watch: acute exercise doesn’t just burn fuel. It orchestrates a molecular choreography so specific, so directional, and so intimately linked to fitness that it reshapes our understanding of what “getting in shape” actually means.

But here is the thing that troubles me, sitting with these supplementary tables spread across my screen at 2 AM: the paper doesn’t mention endocannabinoids once.

This absence is not a flaw. It is a big crack in the wall.

Through that crack, we can see something the researchers never intended to show us.

The Visible Dance

Let me start with what Ambatipudi and colleagues actually measured, because it is remarkable enough on its own.

As your muscles scream for oxygen and your cardiovascular system reaches its limit, something extraordinary happens to the lipid landscape of your blood. The molecules that signal chronic inflammation, a particularly nasty family called trihydroxyoctadecenoic acids (TriHOMEs), plummet. A single molecule, 13-oxoODE, drops with a t-statistic of -22.96. That isn’t noise. That is a biological system actively suppressing a harmful signal.

Simultaneously, other molecules rise. 12,13-diHOME, a lipokine derived from brown adipose tissue that enhances fat oxidation in muscle, climbs. Specific derivatives of arachidonic acid that promote vasodilation and resolution increase. It is as if, in the moment of greatest metabolic stress, your body flips a switch that simultaneously:

- Opens the vascular gates (EETs, certain prostaglandins surge)

- Clears inflammatory debris (TriHOMEs vanish)

- Shifts fuel preference toward fat oxidation (12,13-diHOME rises)

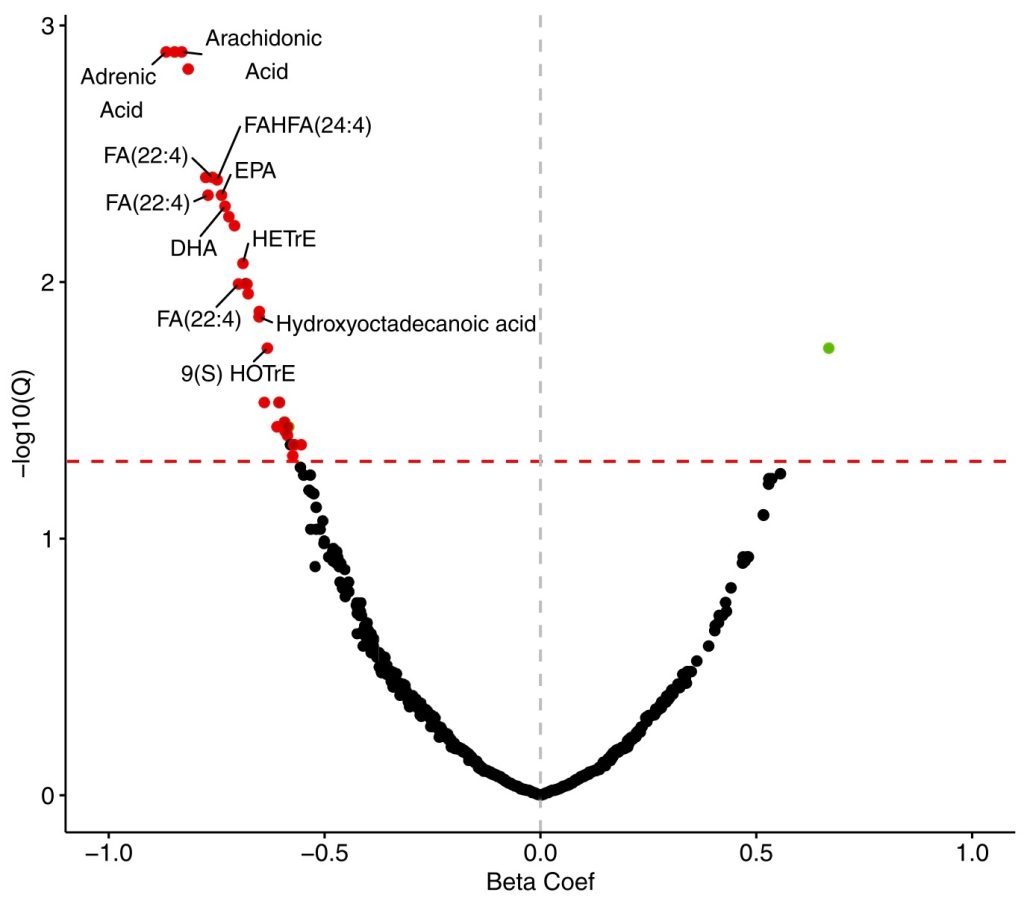

The fitness phenotype (those with higher VO₂peak) execute this switch with a kind of surgical precision. Their “bad” lipids fall faster. Their “good” lipids rise cleaner. In table S4, in the Supplementary Material we see the metabolomic signature of efficiency encoded in beta coefficients: the fitter you are, the sharper your lipid mediator profile during stress.

This is the visible dance. The study captures it beautifully.

But then I notice something in table S3 that makes me pause.

The Disappearing Act

In supplementary table S3, the researchers adjusted their model for RER (Respiratory Exchange Ratio). This means removing the confounding effect of “fuel oxidation.” If the lipids are disappearing simply because they’re being burned for ATP, this adjustment should flatten the signal.

It doesn’t.

Arachidonic Acid (AA) still plummets with a beta coefficient of -0.83. That is after accounting for fuel oxidation. The magnitude of the disappearance is so large, and so poorly explained by the simple “burning it for energy” hypothesis, that I find myself reading the supplementary tables over and over, looking for clues.

Where is it going?

This figure shows the relationship between fold change (log₂ scale, x-axis) and statistical significance (-log₁₀ p-value, y-axis) for 523 lipid metabolites with significant acute exercise response. Metabolites trending downward (left) include trihydroxyoctadecenoic acids (TriHOMEs), arachidonic acid, and EPA/DHA; upward-trending (right) include beneficial oxylipins like 12,13-diHOME and specific arachidonic acid derivatives.

‘Figure 2′ reproduced from: Ambatipudi M, Roshandelpoor A, Guseh JS, et al. The role of bioactive lipids and eicosanoid metabolites in acute exercise in adults: Insights into human cardiorespiratory fitness. Physiol Rep. 2025;13(23):e70671. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.70671

License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The authors suggest it is being converted into eicosanoids. These are the prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and other inflammation-modulating molecules that their panel did capture. Partially, yes. The eicosanoid axis accounts for some of the AA flux. But the sheer volume of the disappearance, especially in the fittest subjects, hints at something else entirely.

Something the panel wasn’t designed to measure.

I think about what happens in the moment your muscles contract maximally. Your intracellular calcium floods. ATP collapses. The cry for relief goes out, and your neurons begin to synthesize two molecules from that same arachidonic acid: Anandamide (AEA) and 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). These are endocannabinoids—the signaling molecules of the endocannabinoid system. They are exerkines in the truest sense: released in response to exercise, they carry autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine signals that reshape metabolism.

We know from other research (Jurado-Fasoli et al., 2022) that these molecules surge during acute exercise. Their levels predict VO₂peak. Their responsiveness defines the fitness phenotype.

But Ambatipudi didn’t measure them.

Not because they weren’t there. Because the microarray doesn’t look for them.

The Ghost in the Machine: Reading What Was Never Written

Here is what troubles me most productively about science: the limits of a measuring instrument become invisible once you design a study around them.

Ambatipudi’s team used a targeted oxylipin panel—a mass spectrometry method optimized to detect the products of COX, LOX, and CYP enzymes acting on arachidonic acid. It is exquisite technology. But it is like trying to map an entire city with a lens that only focuses on streetlights. The street itself may be invisible.

Endocannabinoids are arachidonic acid derivatives. They are exerkines. But they require different extraction chemistry, different ionization modes, and different mass-spec transitions than the molecules in Ambatipudi’s panel. So when the AA vanishes—a phenomenon so statistically robust that it correlates with cardiorespiratory fitness—we are witnessing a metabolic truth that the measurement itself cannot articulate.

This is not the authors’ fault. It is the nature of specialized science.

But if we’re smart enough, we can read between the lines.

Consider this: In supplementary table S1, the researchers listed metabolites that appeared in fewer than 10% of samples. These were filtered out of the primary analysis as “too noisy.” Among these ghostly entries are mass-to-charge ratios in the 407–427 range. These m/z values do not belong to standard oxylipins. They correspond to Prostamides (prostaglandins bound to ethanolamine groups) and Prostaglandin-Glycerol Esters—hybrid molecules created when the enzymes that synthesize prostaglandins encounter not free arachidonic acid, but endocannabinoid precursors.

These molecules were being produced. They were being detected. But they appeared sporadically—only when conditions aligned for their synthesis. In the trash heap of filtered data, we find the fingerprints of the hidden layer.

The Three-Act Structure of the Substrate-Driven System

Now I want to propose a reading of Ambatipudi’s data that the paper itself cannot make.

The substrate-driven endocannabinoid system operates in three nested layers, all fed from the same arachidonic acid pool. To make this intuitive, I will call them:

- The ignition layer

- The circulation layer

- The integration layer

Layer One: The ignition layer (unmeasured, but inferred)

At the moment of maximal exercise stress, neurons and immune cells begin synthesizing endocannabinoids on-demand. Phospholipases cleave arachidonic acid from cell membranes. NAPE-PLD and DAGLα enzymes convert it into Anandamide and 2-AG within seconds. These molecules are exerkines—they create the “runner’s high,” modulate pain perception, and flip metabolic switches from carbohydrate reliance toward fat oxidation.

This is the acute ignition layer: fast, local, and ephemeral.

The Ambatipudi study does not measure this layer. But the disappearance of AA from the blood is consistent with it.

Layer Two: The circulating layer (measured)

Simultaneously, COX-2 and LOX enzymes are working the same arachidonic acid pool. They synthesize prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and specialized pro-resolving mediators. These are the molecules Ambatipudi captures so elegantly. They open blood vessels, modulate platelet function, and signal the immune system to shift from inflammation toward resolution.

This is the circulation layer: it turns a local ignition into a system-wide, sustained response. It keeps the switch “on” long enough for the body to actually do the work of adaptation.

In the fittest subjects, this layer is clean and efficient.

Layer Three: The integration layer (detected, then filtered out)

Sometimes the COX-2 or LOX enzymes don’t encounter free arachidonic acid. They encounter endocannabinoid molecules instead. The result is prostamides and prostaglandin-glycerol esters. These are signaling molecules that carry properties of both endocannabinoids and eicosanoids.

These hybrids are more resistant to degradation than either parent molecule. They signal through multiple receptor systems. They represent a kind of “double transmission,” where the body is saying: this is serious, and we are committed to maintaining this state.

This is the integration layer: it stitches together endocannabinoid and eicosanoid signaling into a longer-lived, multi-receptor control signal.

Ambatipudi detected these molecules sporadically. They appear in table S1 as “high missingness” compounds, filtered out as noise. But they are not noise. They are evidence of a high-flux system under integration.

The fitness phenotype—those subjects with the highest VO₂peak—were likely the ones whose substrate-driven system could orchestrate all three layers simultaneously. Their AA was mobilized efficiently. It was partitioned into endocannabinoids, eicosanoids, and hybrids in the right proportions at the right time. The result: a cleaner metabolic switch, faster clearance of inflammatory precursors, and a more resilient acute response.

What the Data Is Actually Saying

Let me pull back and state this plainly:

Ambatipudi’s paper is not about endocannabinoids. It is about the substrate economics of an acute exercise response. But if we read the paper as a window into substrate flux rather than as a closed system, a story emerges.

The fittest bodies are those that can rapidly convert arachidonic acid precursor pools into signaling exerkines, both endocannabinoids and eicosanoids. This is not a matter of “high levels” of these molecules. It is a matter of rapid mobilization and cycling. The substrate must flow. The signal must be created, transmitted, and resolved. The system that does this fastest and cleanest is the system that achieves the highest cardiorespiratory fitness.

Table S4 proves this. When VO₂peak is the outcome variable, the molecules that predict it most strongly are not the ones that are “high” in the fittest individuals, they are the ones that are cleared most thoroughly. HETrE, EPA, Arachidonic Acid itself, Adrenic Acid: all of them correlate negatively with fitness. The fitter you are, the lower their plasma levels during acute stress.

This is the inverse of what intuition might suggest. But it makes perfect sense if fitness is a clearance phenotype—an ability to rapidly convert precursors into active signals and resolve them.

The Lesson in the Silence

What strikes me most about this paper is not what it finds, but what it inadvertently reveals by not finding it.

Science works within the constraints of its tools. A targeted oxylipin panel is a marvel of precision. But precision in one direction is blindness in another. By designing an experiment to capture eicosanoids, Ambatipudi and colleagues created a window through which endocannabinoids become invisible—not because they aren’t there, but because the instrument wasn’t constructed to see them.

Yet their presence manifests as a ghost in the data. The vanishing of AA. The sporadically detected hybrid molecules. The correlation between lipid clearance and fitness. These are the shadows cast by something that the measurement itself cannot articulate.

This is why I find this paper so elegant, and why I wanted to write about it at all.

It is a study that points beyond itself. It is an invitation to think about the substrate-driven architecture of human adaptation—to see fitness not as an outcome of training, but as an emergent property of a biological system’s ability to orchestrate multiple signaling families from a shared substrate pool.

When you exercise, your body doesn’t just burn fuel. It performs a transformation. Arachidonic acid becomes not just energy, but meaning. It becomes the exerkines that tell your immune system to heal, your blood vessels to open, your muscles to grow. It becomes the endocannabinoids that make pain bearable and pleasure present.

The Ambatipudi paper measures one half of this story. The other half lives in the silence, in the spaces between measurements, in the molecules that were detected but filtered out, and in the substrates that disappeared into transformation.

That is where the real architecture lives.

For the Practitioner: What This Means

If you are training to improve your fitness, what does this paper and its hidden narrative tell you?

Three things:

First, substrate is the script. Your omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid status determines what exerkines your body can synthesize. A diet depleted in these polyunsaturated fats is a diet that cannot generate the molecular signals needed for adaptation. This is not about “reducing inflammation”—it is about having the raw materials for the conversation between stress and growth.

Second, capacity is clearance. The bottleneck to fitness is not how much oxygen your heart can pump. It is how fast your body can mobilize its substrate pools, synthesize the right exerkines at the right time, and resolve them. A training program that enhances flux will enhance fitness more reliably than one that chases numbers. Aerobic base building, which we now understand as training that enhances oxidative capacity and metabolic flexibility, is substrate-flux training. It teaches your system to flow.

Third, the system is shared and integrated. The endocannabinoid system is not separate from the eicosanoid system. They share substrates. They modulate one another. They create an integrated response to stress that is greater than either pathway alone. Training or nutrition strategies that ignores this integration, i.e. strategies that treat “reducing inflammation” as the goal, miss the deeper insight: inflammation is part of the signal. The goal is the integration of all signals into a coherent, adaptive response.

This is what the Ambatipudi paper reveals, and what its silence teaches us.

The paper: Ambatipudi M, Roshandelpoor A, Guseh JS, et al. The role of bioactive lipids and eicosanoid metabolites in acute exercise in adults: Insights into human cardiorespiratory fitness. Physiol Rep. 2025;13(23):e70671.